The Cut-Throat Gig

The Czar has a distinguished history of salvage and rescue. As she approaches her 140th birthday, Tom Matthews discovers how today’s Czar crew are continuing the proud tradition of ‘the cut-throat gig’…

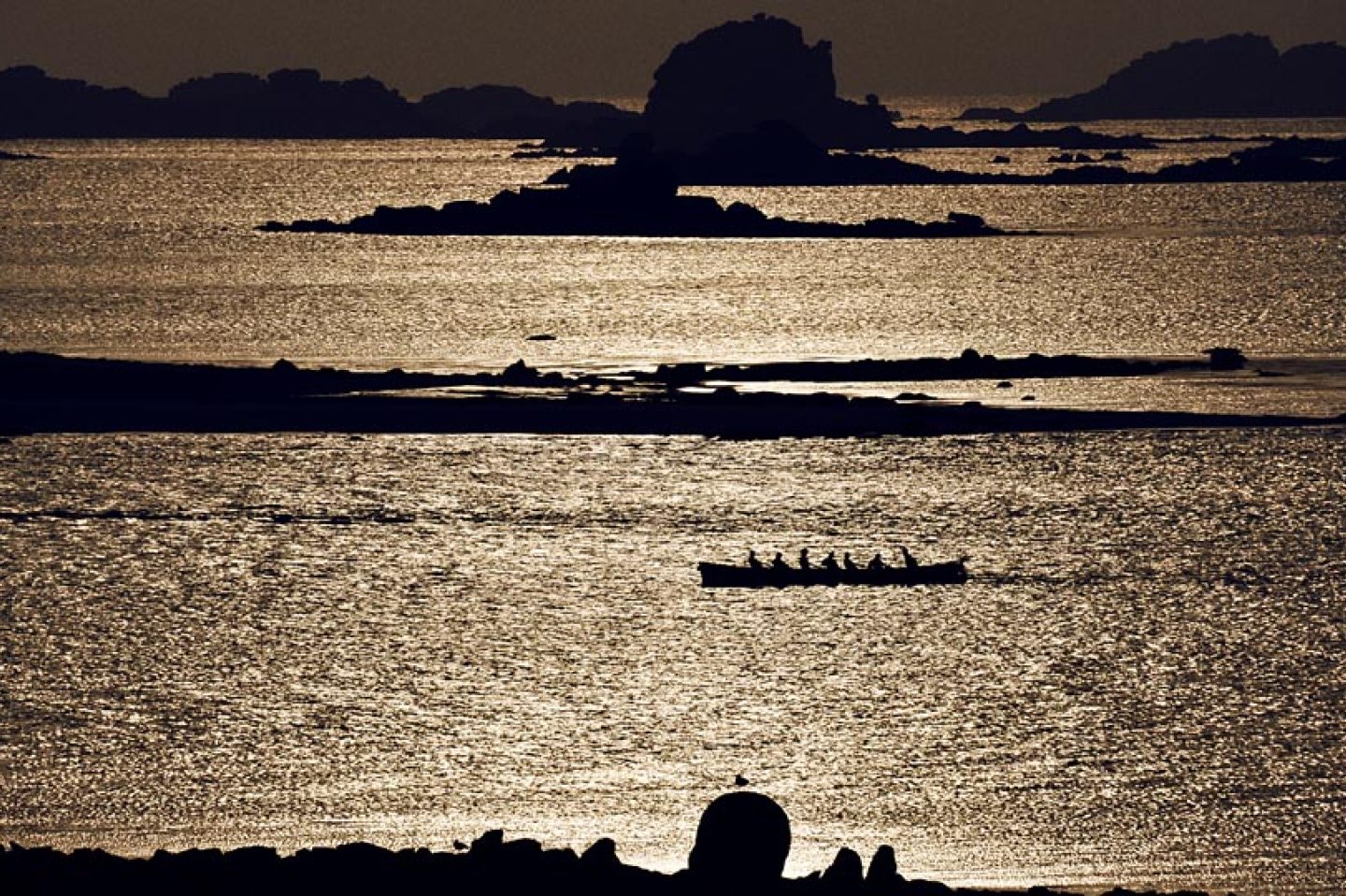

Listen carefully on a calm summer’s evening and you might hear the faint clack of leather against wood; a rhythmic, pulsing sound drifting across the warm summer air. Is it some ghost from the distant past, a gig crew battling to save a vessel in distress on Scilly’s notorious rocks?

“I WANT EVERYTHING YOU’VE GOT – HEAVE!”

The clacking of oars against pins grows louder, faster, more ferocious. Is the vessel foundering?

“EVERY STROKE COUNTS – COME ON!”

Now another sound rolls across the ocean; a straining, groaning, scream of pain. Is it the final cries of the ship as her timbers splinter on some distant granite reef?

“ALL RIGHT GIRLS, WELL DONE. TAKE HER HOME.”

Muscles get their respite; the coxswain rests his voice; the sound of laughter and conversation replaces the groans of exasperation. The Czar ladies of Tresco and Bryher Rowing Club head for home, and their warm-down routine at The New Inn.

Today, the gigs of Scilly may be rowed for pleasure, but the Czar and her sister gigs hail from a time when – as veteran coxswain, rower and master mariner Alf Jenkins put it – “vessels were made of wood and men of iron.”

The first record of a Scillonian pilot gig appears in 1666 – the year of the Great Fire of London – when gigs rescued the crew of the Royall Oacke, which had foundered on Bishop Rock. Originally built to transfer pilots to guide ships through the Scillonian waters, the gigs of Scilly also found purpose as the lifeboats and salvage boats of their day – not to mention the smuggler’s noble steed.

For centuries – long before the advent of flower farming and before the very notion of tourism – pilotage was the mainstay of the economy. In the days before reliable charts and lighthouses – let alone GPS and radar – gigs would race to reach passing ships, securing a pilotage fee which could feed their family for months.

Every island had several gigs, each owned by a family or shared between many. Tresco had the Gleaner, Hope, Longkeel and Swift; Bryher the Albion, Golden Eagle, March, Marene, Sussex, Venus and, of course, the Czar.

With pilotage, the first man aboard got the job, so competition among crews was fierce, and each crew was constantly trying to outdo the others. Often this was through sheer strength, grit and seamanship; at other times helped along by sheer dastardly cunning.

This was certainly the case with the Czar. Built for the Bryher pilots by Peters of St Mawes in 1879, the stated intent of Czar was to outrun another Bryher gig, Golden Eagle. Peters had also built that gig, and such was his pride in her that he reckoned the only way in which she could be beaten was if the new gig was given thwarts for a seventh man. The Czar – nicknamed ‘the cut-throat gig’ – was born.

The very day she arrived on Scilly – 27 July 1879 – Czar was immediately put to the test. Within hours, she was called to the rescue of two ships: the three-masted barque Maipu – wrecked on the jagged teeth of Bryher’s Hell Bay – and the much larger barque, River Lune, broken on the unforgiving granite just south of Annet.

It is, perhaps, fitting that the opening pages of the history of the Czar should be such a story of wreck and bravery. Yes, these boats were designed for boarding pilots to passing ships, but it is for the selfless heroism of their crews in the face of peril that the Scillonian gigs are best remembered.

In his seminal 1907 volume Scilly and the Scillonians, JG Uren wrote: ‘Whatever else may be said of them the Scillonians are no cowards. Manning one of their long, six-oar gigs, and trusting to their skill as boatmen, they will fearlessly put to sea when not even a lifeboat would show her nose.’

There is no record of how many lives were saved by the Czar and her crews over the years – or the riches she brought to the islands in salvage. There is an old Scillonian prayer, spoken by the Reverend Troutbeck: “Dear God, we pray not that wrecks should happen, but that if it be Thy will they do, we pray Thee let them be to the benefit of Thy poor people of Scilly.”

It is, perhaps, ironic that Reverend Troutbeck was the one to utter this prayer. Whilst wreck and salvage did benefit the islanders, it was for his involvement in a very different role of the Scillonian gigs that the parson was allegedly banished from the islands some years later.

Scilly’s location at a strategic crossroads off the southern tip of England meant that ships carrying cargo from across the world passed through these waters. Scilly became a valuable staging post for free trade – or smuggling.

In just six months of 1825, four seizures by the Excise amounted to some 363 gallons of brandy. It was once stated that more contraband was landed in Scilly than ended up at the Excise warehouse in London. Clive Mumford tells us in his 1967 book Portrait of the Isles of Scilly that a bucket of island potatoes could be traded for a bucket of best tobacco (or ‘bacca’ as Scillonians called it).

It comes as scant surprise, then, that alongside their noble lineage of pilotage, provisioning and protecting passing ships, Scillonian gig crews always kept a weather eye on the horizon for a passing East Indiaman, never to lose the opportunity to supplement their meagre island crops.

Over the years, smuggling was challenged by the sheer volume of resources the Excise sent to the islands; indeed in 1828, the Bryher gig Venus and St Mary’s gig Jolly were both confined to port for their habits. The gigs and their crews maintained their nobler, if less profitable, traditions of pilotage and rescue into the first half of the 20th century, but in a changing world of better navigation, and motorised lifeboats (the first arrived in Scilly in 1919), these roles gradually became obsolete.

For the Czar, however, there was to be one final hurrah – arguably her greatest rescue – in dense fog on the evening of 27 October 1927. The Czar – along with motor fishing boats Ivy and Sunbeam – raced from Bryher to the wreck of the steamship Isabo on Scilly Rock. On their arrival, the sea was thick with the Isabo’s cargo of grain, clogging the engines of the motor boats.

The Czar continued the rescue, assisted later in the evening by the St Mary’s lifeboat. In all, thirty lives were saved from the wreck in a rescue that would have been impossible with motor boats alone.

However, the inevitability of time marched on and, in 1938, St Agnes pilot Jack Hicks became the last Scillonian pilot to be put aboard a ship from a gig, bringing to an end centuries of tradition. Over the following decades many gigs were simply left to rot; some were even cut up and used as chicken sheds. Almost all of the traditional Scillonian gigs were lost to woodworm and rot.

“Newquay Rowing Club took the few surviving Scillonian gigs to the mainland and restored them,” says Michelle Oyler, who rows in the Czar today. “The Czar is the only historic Scillonian gig in use today that has remained on the islands her whole life. She’s also probably the most original. She’s had restoration work over the years but there’s still a huge part of her that is the original Victorian gig.

Michelle is certainly an authority on the Czar ; she’s been rowing in her for four decades – not that you’d know it to look at her. Indeed, one of the Czar ladies’ favourite yarns is the time actress Alison Steadman, recording a television interview with the crew, commented that the girls were all “a similar age”. Cue giggles from the rest of the crew and calls of “we do have a grandmother in the gig!”

“That’s why we all keep rowing,” says crewmate Emma. “We all want to still look like Michelle when we’re 50!”

We’re sat in The New Inn, where Czar crews from years gone by gaze back at us from faded black-and-white photographs dotted with the names Pender, Pritchard and Bird. I try to find an image that doesn’t contain at least one Jenkins. In 1964, the Czar won every race, her crew made up of no fewer than three generations of Jenkins: grandfather John, father Dennis and son Stuart.

A stunning pencil drawing of islander Bruce Christopher has pride of place on the inn wall. “It was Bruce that first got me into rowing,” recalls Michelle. “Back in the late ’70s rowing was a male-dominated sport, but everyone knew how to row; it was the only way to get around the islands. One day, around the Czar’s one hundredth birthday, Bruce said to me, ‘Right girl, time you were in a gig!’ I’ve been rowing ever since.”

Ironically, today it is the ladies’ crew that keeps the gig alive; the men’s and ladies’ novice crews row in Tresco and Bryher Rowing Club’s other gigs. The current ‘Czar girls’ consist of Tresco islanders Michelle and Heather, two Emmas (distinguished by the nicknames Emma Flowers and Emma Veg after their respective jobs in the Abbey Garden) and ‘honorary Czar girl’, coxswain Jon. Completing the crew – and continuing the 140-year-old connection between the Czar and her home island – are Bryher residents Jo and Fran.

“Rowing in the Czar makes me enormously proud,” says Emma Flowers. “You look at these old crews and feel a part of history. Every time I get in the Czar, every time I even touch her, I feel proud. Just touching the thwarts, knowing how old she is; how many other people have rowed in her; the conditions they went out in; the lives they saved. We’re still carrying on the tradition – the races we take part in today have their roots firmly in the past.”

Emma Veg agrees: “I recall Steve Parkes saying to me once: ‘You’re part of the history of the Czar now, girl!’ That has always stuck in my mind. It’s just a massive privilege to row in her.”

With such a proud history to uphold, competition for a seat in the gig can be tough. The newest member of the Czar girls is New Zealander Heather, who earned her place in the crew after two seasons rowing in the ladies’ novice crew. So, is she looking forward to the challenge?

“I’m terrified,” she laughs. “I get butterflies just thinking about it, but I also can’t wait for my first season in the Czar. There’s a lot of pressure, though; people look at the Czar and expect the crew rowing her to be good!”

For Heather, it will be in at the deep end; the crew’s first diary date for the year is the World Championships at the start of May. The first ‘champs’ took place in 1990, when a handful of Cornish crews travelled to Scilly and, over a pint or two in the pub, joked: “We should call this the World Championships!”

Nearly 30 years later, some 140 gigs, and more than 400 crews make their way to the islands each year, from as far afield as Bermuda, Holland and the USA.

“It’s like the Grand National on the water,” says coxswain Jon. “The start line is over a mile long with 140 gigs all shouting and jostling for the best place on the line, you’re being blown around by the wind, buffeted by the waves. Then all of a sudden, you’re off. One hundred and forty gigs, each with six paddles, all starting at the same time. The sound is deafening, but you barely hear it because you’re concentrating so hard on what you’re doing – whether that’s rowing or trying to avoid colliding with other gigs.”

Ask anybody about gig championships and – after they’ve finished explaining why they were robbed of a better result – they will talk of the atmosphere. “It’s unlike any other weekend on Scilly,” says Emma Veg. “The racing is sensational, but the atmosphere of the whole weekend is just amazing. You’re all there on the beach, all with a shared passion – you’re literally in the same boat! Everyone helps each other out; you might be fierce rivals on the water, but then you’ll help each other carry gigs up the beach. The competition gets left on the water – ”

“ – Most of the time,” laughs Emma Flowers.

“Champs definitely broadens your horizons,” adds Jo, a Bryher girl born and bred. “You get to socialise with people who you simply wouldn’t meet otherwise, particularly living on a small island. “That’s not just true of the World Championships, though; with our domestic races against the other islands, you all finish up at a pub on one island or another and the camaraderie – not just within crews but between crews – is really great.

“We must be pretty unique – rowing a race, celebrating in a pub on another island, then rowing home by moonlight. That’s the difference with rowing here on Scilly; it’s a social activity first and a sport second. It doesn’t mean we don’t take it seriously; it just means we have fun whilst doing it.”

It’s plain to see this is not just a crew; this is a family.

“Ultimately, rowing is about more than just winning – it’s about camaraderie,” says Cox Jon. The whole crew nods.

“We don’t just row together; we’re really close friends,” agrees Emma Flowers. “There are times when you’ve had a bad day and really don’t want to row, or you’re out in really bad weather, soaked to the skin and feeling distinctly out of your comfort zone, but often those can be the best times as a crew.

“When the crew truly bonds and is perfectly in sync there’s just this indescribable feeling, like a heartbeat, like the gig is alive. It feels like the Czar physically responds, like she lifts, like your spirit and hers sing out with the euphoria of it all. It’s the most indescribable feeling.”

Emma’s reflections remind me of a passage in JG Uren’s book: ‘With long, steady sweep, the boat seemed to bridge over the steepest seas, and propelled by six willing arms to walk the water like a thing of life. If kept head to wind and sea, she will ride like a duck, and shake herself free like a dolphin.’

“It’s the spirit of the Czar, I’m sure of it,” Emma continues. “It’s like the camaraderie of the crew is a thread, running through the ages, somehow connecting us to those days when those brave men would have had to trust each other and the gig implicitly – in the most awful of weather – to save life and limb.”

“When I have enough breath left at the end of a race, I call out to the girls ‘TAKE HER HOME’. To me, that’s what we’re doing: taking her back to her roots, giving her life once more.”